Q&A: Modeling Success with Healthcare Users

Share

The University of Rochester Medical Center’s new Emergency Department and Inpatient Tower expansion is underway, and Principal Thomas J. Parr, Jr., AIA, and Healthcare Planner Gabi Garcia, LEED Green Associate, EDAC, have been deeply involved in the Emergency Department’s early design stages. Ballinger’s expansion and renovation will extend emergency department capacity to 157 single-occupancy rooms and add a new, nine-story tower with five floors of inpatient beds including medical, surgical, and intensive care units. Tom and Gabi shared insights into how early modeling strategies lay the groundwork for informed decisions, leading to enduring large-scale and programmatically-complex buildings.

For projects like the University of Rochester Emergency Department, why is the modeling process so extensive?

Tom Parr: Large projects like these take years and are a huge investment. As a design process advances, changes to the design become more expensive. Modeling allows users to really explore and understand options earlier on, when there’s no cost penalty for changes. We create a number of different models to show changes and also to give users options: people often need different types of models to understand spatial information – not everyone can read plans and understand them. It’s a bit like clothes shopping: some people can understand what a shirt will be like from a pattern or a photo, other people need to try it on. Modeling lets users “try on” the design before they buy it.

“Modeling allows users to really explore and understand options earlier on, when there’s no cost penalty for changes.”

What were the types of models that Ballinger created for the Trauma/EMS groups at Rochester?

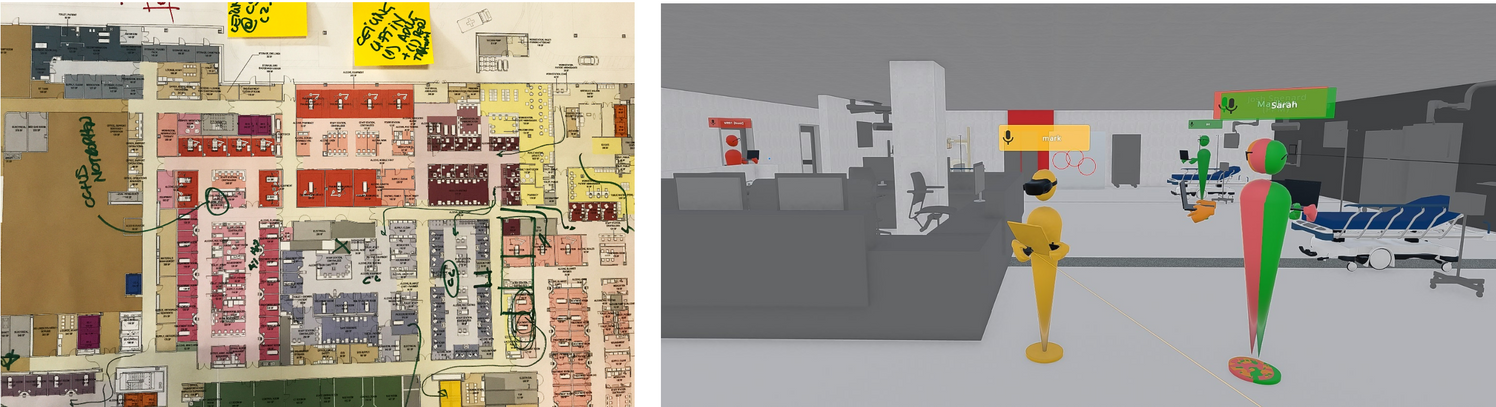

Gabi Garcia: We employed a variety of 2D, 3D, and virtual reality (VR) models. Early on, we got together with the Trauma and EMS user groups – the Trauma Unit staff and the EMS professionals – to draw diagrammatic flow maps based on early discussion of how patients arrive at the existing Trauma Department: by ambulance, via the walk-in entrance, in a mass casualty scenario, and so on. These “day in the life” diagrams, along with patient volume data, helped inform the types and quantities of rooms required for the Trauma program to function.

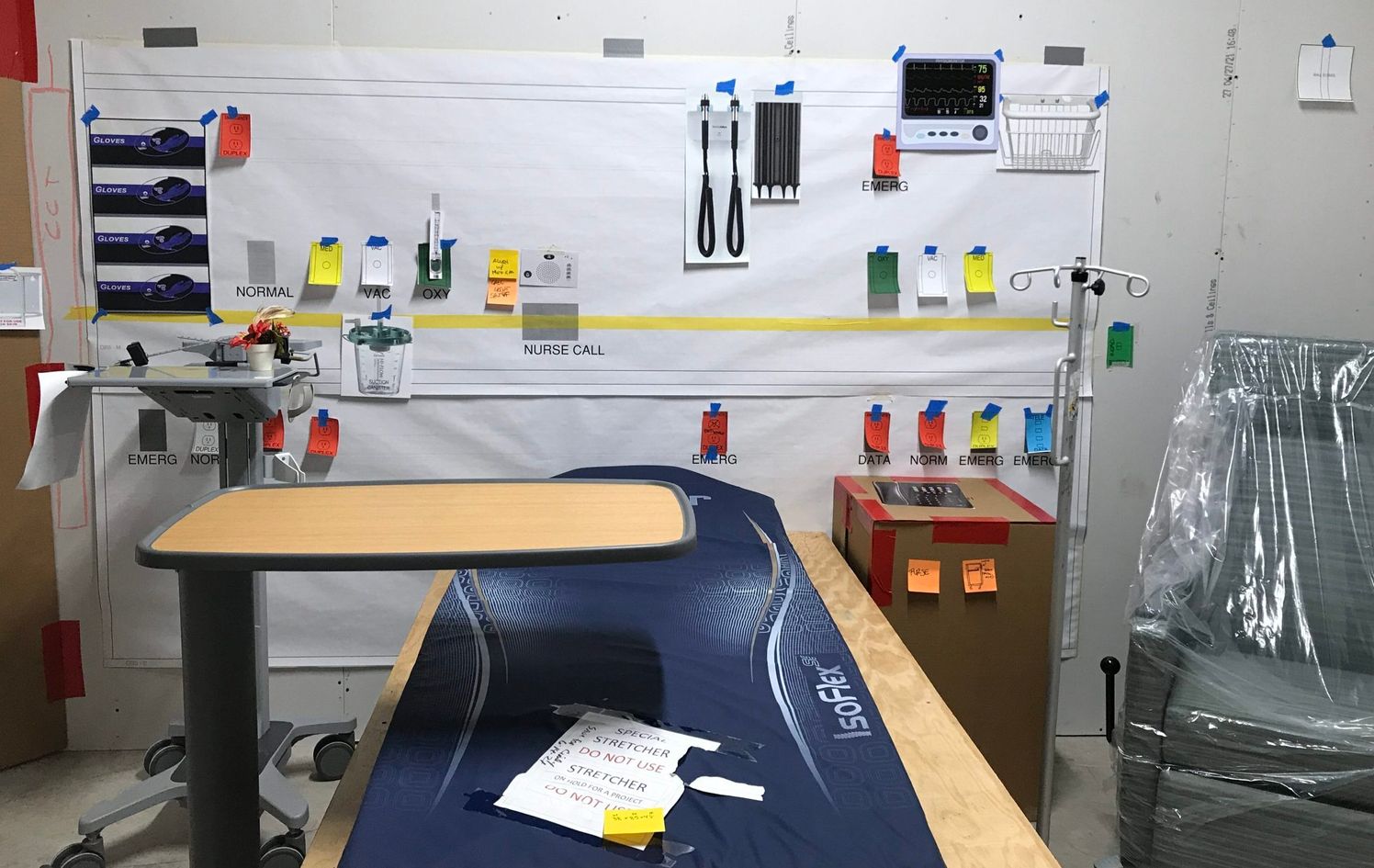

Using the 3D-modeling program Revit, we then translated the Trauma department’s flow maps into virtual floorplan options showing both the interior Trauma department and the exterior EMS ambulance routes. These 3D floorplans introduced entry points, key rooms, and support spaces. We also printed 3D pieces for one of the early user group workshops. In the same way you can set up a dollhouse, we could set up individual trauma bays to show equipment quantities and demands on space, which was helpful to accurately dimension the key rooms.

Parr: That Revit model became the basis for an Enscape model and a VR Prospect model – each of which were informative experiences with the user groups. Each software program allowed users to “move” virtually through space, with and without VR goggles. It’s much more cost efficient to make changes early in the design process, and VR allows users to experience the design before it’s built while changes are still easier to implement.

Garcia: Once the interior space started to come together, we took a closer look at how the larger pieces would move – for example, how ambulances would arrive to the hospital with patients. With the construction team and the Ballinger crew, we set up a low fidelity mock-up that included traffic cones and caution tape. We repeated transportation drive-throughs where ambulances drove through the mocked-up space while the construction team videotaped the process via an overhead drone. That footage, plus surveys from the EMS crew, were used to synthesize feedback.

How did these differ from previous models or modeling approaches for Trauma/EMS client groups?

Garcia: Rochester was actually a VR Prospect pilot project for us – at least in terms of using the software at department scale – and it was also a first for using drone footage as a modeling feedback resource. Since then, we’ve continued to use both in other projects.

Parr: Both applications were extremely helpful additions for a large-scale healthcare scenario. The Prospect VR also allowed us to visualize variations between users (such as an individual’s height or use of space) and the drone footage allowed us to coordinate written feedback with a visual record. At this point drone technology isn’t new, but it’s exciting to see the benefits of new use applications.

What are some of the tradeoffs between scaled physical models and virtual 3D modeling in a healthcare context?

Parr: Physical models are helpful for understanding direct scale: scaled mock-ups allow users to reevaluate common movements and the placement of objects and equipment in a room. 3D models aren’t as physically demanding or cumbersome to build and transport, and they allow users to understand basic flows in a very user-friendly way.

Garcia: We typically use both. Everyone learns differently and for some user groups it can be easier to physically hold a puzzle piece while for others it can be easier to understand space when they are virtually in it.

Ballinger worked extensively with the EMS and Trauma groups at Rochester. What were these groups’ priorities, and how did you address them?

Garcia: For the parking lot, both the EMS and Trauma groups requested that we address backing out versus pulling into spaces, the number of vehicles that will be accommodated, and leveling the parking lot for incoming patients.

Parr: This also tied in to how the parking area would interface with the Emergency Department entrance: for example, will we accommodate stretcher with curb cuts? No curb at all? When EMS personnel are transporting patients to the building, would overhead protection inadvertently create a wind tunnel? There are a number of factors to consider, not just the route a patient will take to get from an ambulance to treatment.

Garcia: I’d also add that the client wanted to be prepared for a mass casualty scenario, so understanding how that would impact space was important, too.

How many iterations of the EMS/Trauma flow were considered before setting on the final layout, and why was the final layout selected?

Garcia: A ton! Floor plans are almost never one-hundred-percent settled. While we try our best to gather as much possible information during the early phases of a project, we’re always learning.

Parr: And the user groups are also always learning and evolving. The final selection represents the best balance of understanding how space is currently used and how it could be used in the future.